The essentials of intellectual property

Intellectual property is all about the legal protection of 'the good idea'. It’s the area of law that enables designers, innovators and other creative people to protect and exploit their work and to prevent misappropriation by others. The economic and operational fallout can be disastrous for anyone failing to properly protect their IP.

Intellectual property protection involves granting exclusivity to the rights holder in relation to protected property. This can then be exercised to prevent third parties from copying, manufacturing or adopting features of the relevant designs or technology. Conversely, failure to obtain protection can leave materials vulnerable to these types of unauthorised acts, and the designer or innovator unable to prevent such use or claim any payment for it.

Intellectual property law is made up of many elements of legal protection and a design or technology owner will be concerned with any number of them. They include:

- Patents

- Copyright

- Registered design right

- Unregistered design right and

- Trademarks

In more depthFind out how inventors can use IP more effectively in our

Invention article by experts Graham Barker and Peter Bissell

Patents protect 'inventions'. These include mechanical processes or devices. A patent must be applied for in each territory (country or group of countries) where exploitation is intended to take place. It will be subject to establishing that the relevant invention is new, that it involves an inventive step and is capable of industrial application. Once granted a patent lasts for 20 years, following which the invention passes into the public domain. If an invention is published or marketed without the benefit of a patent and the new inventive functions are openly discernible, then they will not enjoy any intellectual property protection. They will have been placed in the public domain.

Copyright is the exclusive right of an individual to copy and otherwise exploit, among others, 'literary works' and 'artistic works'. It protects, for example, computer software, works of architecture, surface decoration applied to manufactured articles, text, manuals, drawings and other documentation, as well as the artistic aspects of product packaging. It protects the form or expression of a work rather than the idea underlying it. It lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years. Copyright comes into being automatically when the relevant work is created. It does not need to be registered. 3-D articles will only normally be protected if they are 'works of artistic craftsmanship'.

Unregistered design right protects aspects of the shape and configuration of an article. The maximum life of design right is, in practical commercial terms, 10 years. The right subsists either from when the design is recorded in document form or from when an article is made to the design. The design may be copied in the last five of those years if the copier agrees payment of a reasonable royalty. That is the position under UK law. From 6 March 2002 an EU-wide unregistered right (but protecting similar types of designs to the registered right, as described below) came into effect. This provides protection for three years from the date the relevant design was made available in the EC. November 2003 saw the first Community design infringement ruling in favour of Mattel.

Registered design right provides further protection for the appearance of the whole or part of a product arising from, for example, the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture or material of the product or its ornamentation. It can also protect desktop icons and graphical user interfaces (GUIs). The rights must be applied for and registrations can extend for up to 25 years, i.e. significantly longer than the unregistered right. Community law provides for an EU-wide registered right. From 1 January 2003, the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM) has accepted applications for these registered 'community designs' and has been examining applications since 1 April 2003. Community-wide protection can be obtained with one application.

Trade marks are words, logos, devices or other distinctive features which can be represented graphically and can distinguish goods or services of one business from those of another. They can consist of the shape of goods or their packaging. Registration of such marks can and should be obtained and, subject to payment of renewals, can be indefinite. Without registration trade marks can still be protected in certain circumstances, through an action for 'passing-off'. This is a more complex (and expensive) process than a registered trade mark infringement action, however and requires the claimant to prove that it has a reputation associated with the mark and that the public is confused.

The intellectual property protection for any given product will in most cases be a combination of the different rights listed above.

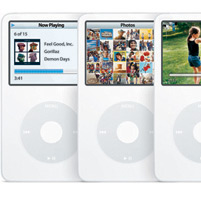

For example, an iPod will comprise mechanical features which could be protected by a patent; it will comprise physical design elements which will be protected by unregistered design right and features of the appearance of the item may be capable of supporting a design registration; the packaging and manuals will be protected by copyright; and the brand itself ('iPod') will be a trade mark. An appraisal of what protection is appropriate should be an integral part of every product launch or refresh.

For example, an iPod will comprise mechanical features which could be protected by a patent; it will comprise physical design elements which will be protected by unregistered design right and features of the appearance of the item may be capable of supporting a design registration; the packaging and manuals will be protected by copyright; and the brand itself ('iPod') will be a trade mark. An appraisal of what protection is appropriate should be an integral part of every product launch or refresh.